This blog is written by one of CUCo’s affiliated researchers

Setting up interdisciplinary research teams usually requires nurturing the relationships with creative processes. During these processes, an uncomfortable question can bug some of the team members: are they busy making cathedrals that last beyond their creators’ lifetime, or sandcastles that could be washed away by the next tide?

By Sanli Faez (Professor (UHD) at Utrecht University and member of the Fair-Battery Challenge team)

Process or output?

Forming inter- and trans-disciplinary teams requires patience and thinking outside the box. It demands a lot of effort for team-building in order to find a common language for communication and create the learning conditions for each of the team members. This difficulty, however, should not stop us from trying to execute such projects. Most complex problems do not fit into a single discipline, and reducing these problems into simplified models that match a classical methodology can yield solutions that nobody benefits from. Interdisciplinary insights coming from research, when executed rigorously and in connection with the problem owners, can create a durable impact and real progress. However, the actual details of this approach can become so much dependent on the context that the learning outcomes are deemed too project specific to be relevant outside the original context, and hence untransferable.

In the academic context, the necessary emphasis on the process of interdisciplinary work must stay in balance with creating objectively transferrable outcomes that persist beyond the scope of the project. Otherwise, the benefits could stay limited to the team-members or their immediate surrounding. The teamwork required for interdisciplinary projects can demand a lot of communication and creative co-experiences which are varied in their form and medium. Conventional academic outputs like articles and presentations cannot always serve as a good vehicle for transferring these outcomes. In the extreme case, doing interdisciplinary work can become an artisan practice that can only be “experienced”, but not taught. However, if the learning outcomes of an interdisciplinary project can be only based on participation experience and person-to-person communication, their diffusion will definitely be much slower than the disciplinarily classified knowledge, which often propagates by means of texts and seminars. There is risk that an “interdisciplinary wheel” has to be reinvented over and over again.

Which reports are valuable?

Focused on this question, I facilitated an hour of participatory workshop during the CUCo community day. With seven participants from diverse disciplines and backgrounds we used the “Cycle of Grief” tool (adapted from the Genuine Contact program, by Brigitte Williams) to first uncover what feels wrong about the reporting process of interdisciplinary projects and what feels right when going down that memory lane. In smaller breakout groups of 2-3 persons, we gathered our memories from writing and reading project reports and classified them as those making us “Sad”, “Mad”, or “Glad”. When comparing these notes, we could share our intuition about what a good report should be and how can a group be encouraged to write such a report.

A common reflection was that a good report highlights the learning process, and even includes the mistakes or failures. Such a report is varied in style and matches the context of the project. Sometimes, a written output that comes out of the conviction of the group feels richer than the format imposed on the team by the project sponsors, while other times a proper guideline and template can be very helpful in properly summarizing and classifying the outputs of the project. On the other hand, too long reports with forced section headers that feel like forcing the writer to tick boxes are the most despised. A balanced report, in the view of some workshop participants, is brief, combines facts and practical guidelines, and is aimed at learning.

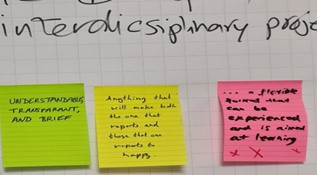

The first part of the workshop was aimed at sharing intuitions and emotions, aside from rational thinking. After discussing our experiences and “grief” of previous reporting experiences with each other, it was time for convergence. For this exercise each participant suggested a minimal second part for replacing the three dots in the following statement:

“A lovable report of an interdisciplinary project is…”

After a simple voting process, the majority of the participants choose this statement: “a flexible format that can be experience and is aimed at learning.”

“A lovable output of an interdisciplinary project is in a flexible format that can be experienced and is aimed at learning.”

We closed the workshop with a talking stone ritual, during which each participant shared their take-home insight from this hour. The prevailing shared insight was that of a positive motivation to think constructively about reporting on projects.

Besides the positive experience of the participants, this blogpost is the main outcome of this session. One hour is certainly too short to create general advice for the large and rich field of interdisciplinary project management. We could only make a first step grounded on our own experiences.

By publishing this post, I invite other CUCo teams to dedicate a regular reflection time on analyzing the suitable output of their project that can last longer the duration of their project.