The Centre for Unusual Collaborations (CUCo) advances knowledge and learnings on processes of inter- and transdisciplinary collaboration by collecting and analyzing team experiences at various funding stages. These insights showcase the value of such research to researchers and policymakers, highlighting challenges and barriers to influence and improve research policies at knowledge institutions. Interviews with CUCo teams demonstrate the impact and importance of interdisciplinary work, aiming to lower barriers and foster collaboration across disciplines.

This time, CUCo spoke with Hanneke Willemen (UMC Utrecht) about the collaborative process and interdisciplinary work of the Defeating Chronic Pain team which resulted after the funding period at CUCo, into building the iPOP-NL Interdisciplinary Pain Research Platform. Team members are Sylvia Brugman (WUR), Yoeri van der Burgt (TU/e), Tessa van Charldorp (UU), Frank Meye (UMC Utrecht), Laura Winkens (WUR), Mienke Rijsdijk (UMC Utrecht), Jannie de Grauw (UU) and Madelijn Strick (UU). Meet the team!

Written by: Helma van Luttikhuizen

First things first: could you tell us who you are as a team, how it all started and what excites you about working together?

In 2019, we initiated our journey at an event organized by CUCo that brought together individuals from Young Academies and others interested in unusual collaborations. I, as a fundamental scientist on chronic pain, went there along with clinical pain specialist Mienke Rijsdijk, since we recognized the need to work closely together to address the complexities of chronic pain. However, we realized that tackling such a multifaceted issue requires collaboration across multiple disciplines. At the event, we shared our idea and invited others to join us in brainstorming how we could form an interdisciplinary team to understand more about the complexities of chronic pain.

We discovered our common interest through the story of a young mother who, due to chronic pain, could no longer care for her children. This resonated with all of us. Chronic pain is a widespread issue, affecting around one in five people at some point in their lives. Many of us have personal connections to this struggle, whether through people dealing with conditions like migraines or arthritis, or through own experiences. This personal connection, alongside the staggering numbers, really brought us together to tackle this issue.

Over time, our team grew to include nine researchers from different universities and fields, and we began the process of writing our CUCo grant proposal together, with the main aim to see how we can defeat chronic pain. We have a really diverse group, including a linguist, an anesthesiologist-pain specialist, a behavioral scientist, a neuroscientist, and we have a mechanical engineering scientist. We have even got a veterinary anesthesiologist on board since there are parallels in pain between humans and animals. Other team members include a psychologist, an imaging expert, an immunologist microbiome expert and me as molecular biologist.

Your collaboration started in 2021 with the support of the Centre for Unusual Collaborations grant. Could you tell us a bit more about the journey of your team as of the start of the project until now?

The process itself is really interesting. One of our team member suggested that we write a paper about our experiences throughout the process, particularly highlighting the challenges and ‘uneasiness’ we faced as an interdisciplinary team. We realized that while many people talk about the importance of interdisciplinary research in being beneficial for all kinds of problems and diseases, not everyone understands the complexities involved (*to read the full paper, please find the link at the bottom of the page).

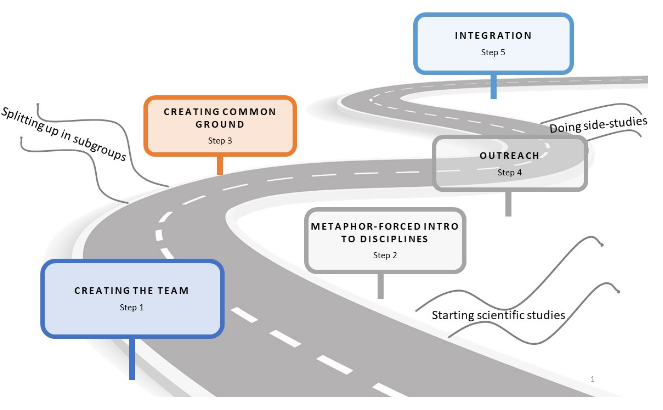

For example, in the early stages after receiving CUCo’s grant we encountered significant communication barriers. Although we are all academics and all speaking Dutch, we struggled to understand each other due to the different “languages” we spoke within our fields. The pain experts tended to dominate the discussions and the rest of the team was more like ‘what is going on?’. Quiet soon we realized we are all academics, but we really cannot understand each other and we decided to start the journey to get back to the basis: what is the common ground and how can we really understand each other? To tackle this, we got creative and used metaphors and household objects to explain complex concepts across disciplines. For example how can I explain as a molecular biologist to a psychologist what I am doing in the laboratory? This helped us to find common ground. We also eventually brought in a facilitator to guide our discussions, ensuring everyone was on the same page. The facilitator helped us articulate our reasons for choosing chronic pain as our focus and encouraged us to define our shared understanding of the subject. By working together, we created a unified metaphor for chronic pain that everyone could grasp. From there we really started the project, almost one year later.

Can you elaborate a bit more on the final metaphor your team settled on and how it relates to your research on chronic pain?

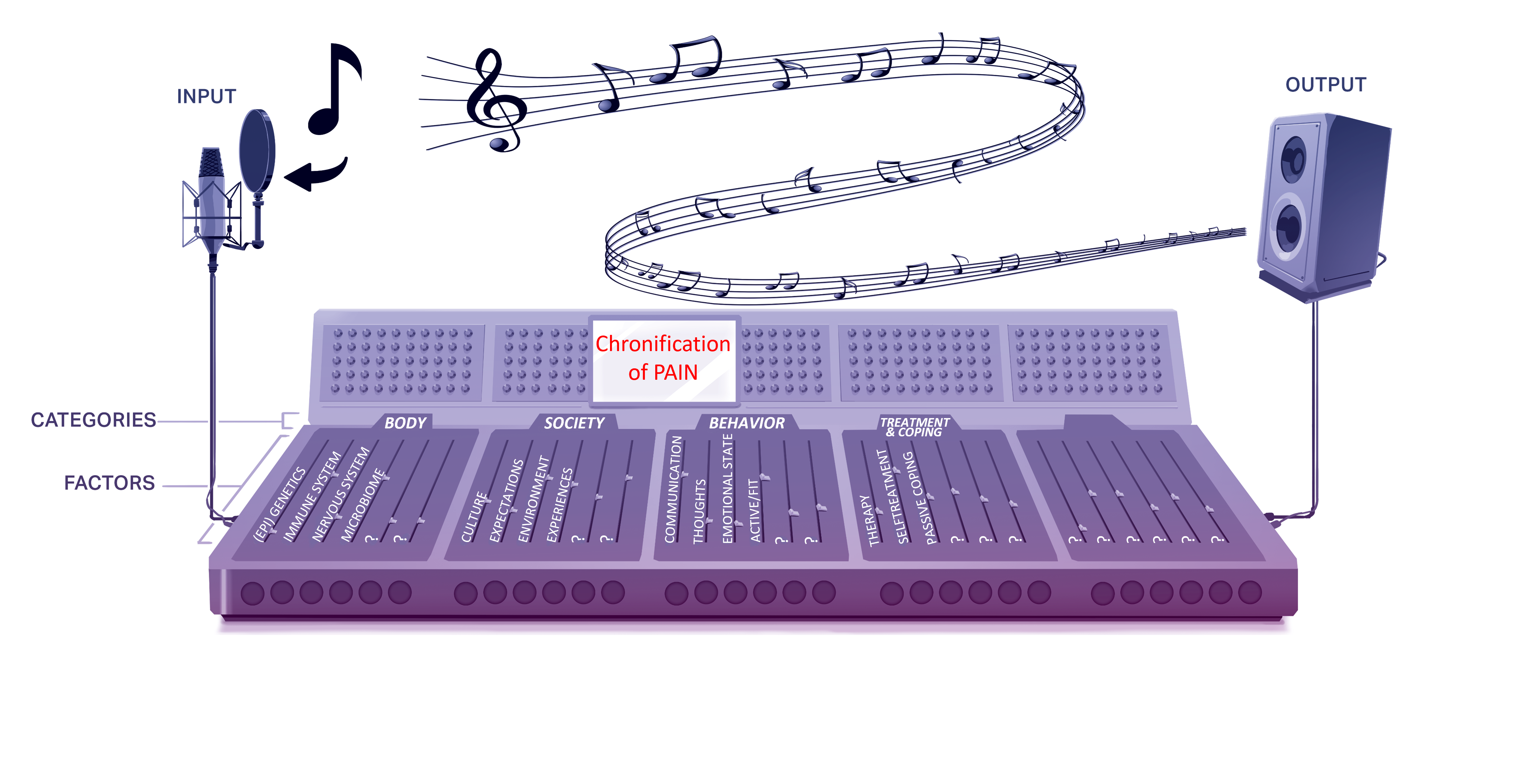

We ultimately chose the metaphor of a DJ mixing table to represent our interdisciplinary approach. Just like a DJ uses knobs and sliders to mix different input signals into a cohesive output, we believe that each individual also has certain sliders and knobs that influence pain perception. As such, understanding how and which factors influence pain perception is crucial. For example, when someone experiences acute pain, it may resolve quickly due to various factors (often biologically, since the injury heals or inflammation subsides). However, due to underlying factors—like genetics (e.g. mutation in a gene), psychological state (e.g. anxiety/depression), or social circumstances (e.g. lifestyle habits)—, acute pain can evolve into chronic pain, which has consequently large psychosocial impact, thus creating a vicious cycle. This perspective helps us understand that the initial cause of pain might not be as significant as the ongoing influences that maintain it. As we explored this metaphor, we recognized that our goal would not necessarily be to “defeat” chronic pain, but to improve management and quality of life for patients.

With around 80% of patients expressing dissatisfaction with pain management, we see potential in analyzing these “sliders” to find new ways to prevent chronic pain or develop more effective treatments. What I really appreciate about our collaboration is the holistic approach we take as a team. For instance, while I, as a molecular biologist, might focus on genetic factors, our linguists emphasize the importance of communication with patients. Oncologists for example often overlook pain management in favor of assessing whether a tumor is gone, but by asking about pain early in treatment, we could intervene more effectively to prevent it from becoming chronic. Another example is that we collaborate with mechanical engineers to explore ways to measure pain objectively, given its subjective nature, like traditional pain scales can be challenging for patients with communication disabilities. Overall, our discussions have led to several projects aimed at enhancing our understanding of chronic pain and its management, highlighting the importance of our interdisciplinary approach.

How has this interdisciplinary collaboration shaped your perspective on your own disciplinary background. What did others allow you to see that you did not see before?

It kind of makes me feel insecure in a way, realizing you cannot do it alone. As a molecular biologist, I realize that solving complex problems, like diseases, cannot be done alone or within just one discipline. I know a lot about the nervous system and its activation, but I really do need other disciplines. I believe this is essential for real progress. During my upcoming VIDI interview, which is a personal grant interview about pain research, I want to emphasize that team science is really needed and necessary to combat these challenges. I will use my experiences I got throughout this journey with the Defeating Chronic Pain team to explain that. I hope that by taking this approach, which is different from the usual individual focus, they will see the value in it and award me the grant (update 22-10-24: the grant has been awarded!). I feel like I am becoming more of an activist, standing up for the importance of changing how science is done. It is not just about me being the first or last author or having my name on the lab—it is about team science and the fact that no one can do it alone.

Imagine iPOP-NL will be funded for the next 10 years. What societal change would you like to contribute to and which challenges do you see to get this project funded?

One of the challenges as an interdisciplinary team is to find funding resources. We struggled with how to apply for the Ammodo Science Award, for example. We had to choose a specific domain, even though our team spans biomedical sciences, humanities, natural sciences, and social sciences. We eventually chose a category, were nominated, and proud of that, but eventually did not get it. This highlighted the challenge of fitting interdisciplinary work into traditional categories. It is hard to get support for interdisciplinary research, and while we continue trying, we are often pushed to break our work into smaller, domain-specific projects. The work we are doing now—like investigating chronic pain subgroups using data from various fields—would not be possible without collaboration across disciplines like psychology and lifestyle studies. I think that without this interdisciplinary collaboration, progress would be slower and the impact smaller.

Additionally we aim and continue to create awareness on chronic pain, a condition that affects so many people, yet students and the public know so little about. We have held interdisciplinary seminars for students from different fields, encouraging them to think creatively about how chronic pain affects patients. We have also extended our outreach to the public through festivals, podcasts, magazine articles and we launched a platform called iPOP (Interdisciplinary Pain Research Platform) to bring together patients, clinicians, researchers and others to engage people in the broader conversation around chronic pain.

In ten years, it would be great if we can contribute to personalized pain medicine. We have already developed a tool that helps clinicians categorize chronic pain patients based on psychosocial questionnaires. This tool can eventually help to decide if a patient will benefit of a more multidisciplinary treatment instead of pain-medication alone. With additional data from blood markers or neurological studies, we could advance personalized medicine and enhance pain management with greater precision. While we currently focus on symptom management, it would be really interesting to understand how the body naturally shuts off pain to develop new drugs that promote this process. We are collaborating with the radiology department to scan patients and track their pain progression, aiming to identify markers that predict pain recovery and support early intervention.

However, securing funding remains our challenge. We have tried crowdfunding via Give for Chronic Pain facilitated by the Utrecht University Fund, which has raised about 16,000 at the moment, and we are waiting to hear about a NWO team science award in November that could provide additional support. Even though our team funding from CUCo ended, and despite the funding obstacles, our team is still committed to work together. We all see this as a creative, outside-the-box project that brings us joy because of the interdisciplinary learning and lack of pressure to produce immediate results. The freedom to explore interdisciplinary work is what I value most, but it is often constrained by academic roles and funding structures. I am trying to change that by pushing for more team science, where collaboration across different fields can lead to more holistic solutions for complex problems like chronic pain.

What do you know now about collaborating across disciplinary boundaries that you would loved to know at the start of the project?

When we started our interdisciplinary research, I realized that navigating the different backgrounds and terminologies of our team members was a significant challenge. Initially, I thought that collaborating with other academics from diverse fields would be straightforward. We all had a shared goal, and I was optimistic that we could achieve what we set out to do within a year. However, I soon learned that it was not as easy as I had anticipated, and that each discipline has its own language and way of thinking. There is an emphasis now on training to help teams communicate effectively and find common ground, which we lacked in our initial experience. I am glad to see that future interdisciplinary teams at CUCo can benefit from this knowledge.

*Read the paper: Uneasiness in interdisciplinary research and the importance of metaphors: a case story on building an interdisciplinary chronic pain research team