The Centre for Unusual Collaborations (CUCo) advances knowledge and learnings on processes of inter- and transdisciplinary collaboration by collecting and analyzing team experiences at various funding stages. These insights showcase the value of such research to researchers and policymakers, highlighting challenges and barriers to influence and improve research policies at knowledge institutions. Interviews with CUCo teams demonstrate the impact and importance of interdisciplinary work, aiming to lower barriers and foster collaboration across disciplines.

CUCo’s grants

CUCo offers two types of grants: Spark grants and Unusual Collaborations (UCo) grants. Spark grants are designed to stimulate unusual collaborations addressing societal challenges by providing initial financial support. This allows teams to build a committed project team, explore ideas, and test their potential for further development and funding applications.

Spark teams can apply for an UCo grant, which is designed to advance projects through outside-the-box inter- and transdisciplinary research with societal relevance. UCo grants support unconventional research that would not easily get funded through other funding schemes. They provide one year of funding, with the idea that projects will continue beyond this period. Teams can reapply for UCo funding for up to three years; applicants are also strongly encouraged to explore other funding avenues for sustained support.

Explore CUCo and Spark grants to ignite your interdisciplinary research and collaboration!

This time, CUCo spoke with Mehdi Habibi (WUR) about the collaborative process and interdisciplinary work of his Smart Food team, which also consists of Guido Camps (WUR), Tina Vermonden (UU) Riccardo Levato (UU), Caroline Lindemans (UMCU), Betina Piqueras Fiszman (WUR) en Yann de Mey (WUR).

Written by: Helma van Luttikhuizen

First things first: could you tell us who you are as a first-year UCo team, what excites you about working together and what you are working on in the Smart Food project?

The idea for this project originated four or five years ago, focusing on interdisciplinary research as a starting point. Inspired by my previous research on metamaterials or making materials that respond to stimuli, the idea was to create a smart, functional material that you can swallow, which would then open up inside the body, for example in the stomach, and perform a specific function.

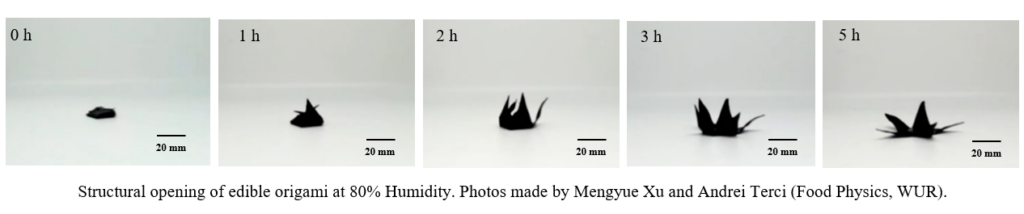

Over time, a team was formed, including colleagues from various disciplines, to refine this concept. We developed initial prototypes using edible materials. The current prototypes are too large to be swallowed, and cannot yet be deployed inside the body. Efforts are ongoing to make them smaller. Through collaboration across diverse disciplines, we have uncovered the potential of smart edible materials, offering benefits like appetite control, nutrient release, and targeted drug delivery.

To assess feasibility and consumer acceptance, team members Yann and Betina are conducting a survey to understand public perception, recognizing that the acceptance of ingesting smart foods may differ from other technologies. Their survey also seeks to identify potential risks and challenges if the technology is not accepted by consumers. This early feedback will help integrate public concerns into the project design and communication strategies.

Beyond appetite control and nutrient release, we are also exploring applications for drug delivery for inflammatory diseases in the gut. This involves determining the system’s activation location and necessary stimuli. Currently, just a few weeks ago, we have developed prototypes using edible materials like gelatin sheets and created origami structures capable of opening up, demonstrating progress towards their goals.

Watch this video to learn more about the Smart Food project. This video was made during the Spark phase.

How has the granting process of the Centre for Unusual Collaborations affected the nature of your research? Does it differ from other grant processes you have applied for?

This granting process is definitely different from the current schemes and comes with its own upsides and downsides. The design of this granting process allows for starting from an idea and developing it through identifying required collaborations and expertise, which differs from many other funding schemes that require specific targets, low-risk, feasible projects, and addressing specific problems within a set timeframe.

Can you tell us about how you have formed the team and the process?

We did not design the process that much initially. As for the first few members: I had some ideas that had essential links with another discipline. So we started by considering key members for the consortium. The rest grew organically. Some members joined and later left due to job changes, relocations, or moving to different institutes. Others had busy schedules beyond what they could commit to our project.

Now, after two to three years, we have a balanced team with different disciplines. It’s specifically nice to have Betina and Yann onboard, because initially it wasn’t clear to us how to integrate all of our findings. However, after several meetings and discussions about capabilities, needs, and the societal implications of our work, we have realized the importance of incorporating expertise from social sciences, which Betina and Yann bring to the team. Understanding how society perceives our technology is crucial for our next steps in addressing societal issues.

How is the UCo stage different from the Spark phase?

During the Spark phase, discussions with the team were more casual, and focused on interesting ideas without a clear plan for action. We had many brainstorming sessions during this phase. What really solidified our ideas and planning was visiting each other’s labs. Seeing firsthand what each team could do was crucial. For example, one team could easily 3D-print biodegradable or biocompatible structures, while another team had expertise in loading them with drugs and studying drug release. This clarity showed us how these different elements fit together, forming a solid foundation.

Receiving funding through the UCo grant was a turning point. It motivated everyone to invest more time and effort. With funding secured, I allocated one of my PhD students to dedicate half of their time to designing origami-like structures that could unfold. This effort resulted in a tangible product, marking a significant milestone.

Currently, we are at the stage where we are further refining our project . As mentioned before, we are conducting a survey that will be completed in a few month, and we already have some concrete results from it. We have also developed prototypes using various materials. Additionally, colleagues at Utrecht University, including Tina, are focusing on the release aspects. In September this year, my PhD student will visit them to conduct release experiments on our prototype.

Imagine Smart Food will be funded for the next 10 years. What societal change would you like to contribute to?

There are at least two clear ideas for addressing societal challenges with this system. First, it aims to provide tailor-made and programmed drug release for inflammatory diseases in the gut and stomach. This involves covering wounds and releasing drugs in a programmed manner at the right time. Additionally, the system can be extended to address malnutrition and obesity. I have had initial discussions with IMEC, a company interested in using high-tech technologies to address health and nutrition issues. I believe our projects could be integrated, allowing us to combine our technologies. Hospitals are also likely to be interested if we can develop a functional prototype, opening up further opportunities for collaboration.

Addressing obesity with this technology could possibly attract interest from pharmaceutical and food companies. But for now, we are just taking smaller steps. And if we can reach what we aim for, then I think they will come to us.

Which challenges do you see to get this project funded for the next 10 years, after CUCo funding ends?

I think several challenges must be addressed. First of all, in order to really make a difference, the challenge is to find the right funding to support the project long-term. We have not yet found a specific grant that fits our project. Another idea is to split the project into smaller parts, each targeting different funding sources. Going for smaller, more specific funds might help us to continue, but it could also make the project less cohesive.

Secondly, getting colleagues to invest time in a project that is not their primary focus, is challenging. Many view this as a side project, which limits the time and effort they can contribute. As the project progresses and demands more investment, this challenge could become more pronounced. Securing funding that can cover part of their work hours might mitigate this issue.

While involvement of various disciplines allows for diverse contributions, it also means that the project cannot be the primary focus for everyone involved. The traditional structure of universities, which often consists of specific research groups focusing on particular topics, limits the flexibility needed for interdisciplinary research.

What needs to be changed to overcome these challenges?

I think that, in order to promote interdisciplinary research effectively, universities need to adopt more flexible structures that allow for significant overlap between research areas. Financial considerations are also crucial. Although we have received funding from CUCo, we still face challenges in allocating resources across different departments.

Furthermore, we need to talk to policymakers and funding organizations to create funding schemes that support long-term, interdisciplinary projects so that they can really make an impact. Addressing these issues will be crucial for these projects’ success, and for fostering a more conducive environment for interdisciplinary research in general.

What do you know now (about collaborating across disciplinary boundaries) that you would love to have known at the start of the project?

A key takeaway is that this kind of research is not easy. It demands significantly more time and effort compared to normal projects. As project lead, it also takes a lot of time and effort to keep team members motivated and engaged. Regularly sharing new results helps to maintain motivation and participation. Creating tangible prototypes, for example, makes abstract concepts more concrete and feasible for the team.

I believe that it is important to share these insights with others – especially the next generation of researchers. They need to know beforehand how to develop certain communication skills, and that different disciplines have different ways of thinking. For example, we are now thinking about a workshop tailored to PhD students during a symposium we want to organize.

I hope that we can share our experiences – with the help of the expertise gathered within the Centre for Unusual Collaborations – specifically with next-generation researchers. I think the future of the research is probably multi- or interdisciplinary and having basic knowledge about these competences is essential.